Hindsight, we are told, is a wonderful thing. In many ways, it is. But in some ways, it can hinder our view of the world.

Over the past few years, I have been part of a team researching the changing Continue reading Hindsight

Hindsight, we are told, is a wonderful thing. In many ways, it is. But in some ways, it can hinder our view of the world.

Over the past few years, I have been part of a team researching the changing Continue reading Hindsight

We are slowly becoming accustomed to the idea that the world experienced by our ancestors was very different to our own, even within the span of a few millennia. Nowhere is that made clearer than when standing among the remains of a long-dead forest, especially when it lies in a landscape devoid of trees. Continue reading The Forests of the Sea

The submerged landscape touches us all, wherever we work. We need to bring a basic understanding of the original lie of the land to our site analyses. However, therein lies a problem. In many places, current understanding of the past position of the Continue reading The limitations of modelling

Just to flag up a new paper that I have been working on with colleagues which has recently been published. It is in an expensive volume (apologies), the first of three. It is a series which will be useful, so persuade your university to get the books for the library. I note that all are available as ebooks, though the price is the same! This work was undertaken while I held a personal fellowship from the Leverhulme Trust – my thanks must go to them for enabling the research!

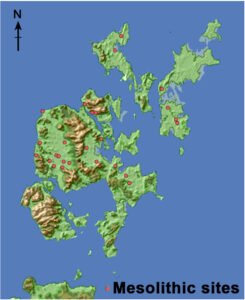

Wickham-Jones, C. R., Bates, R., Dawson, S., Dawson, A. and Bates, M. 2018. The Changing Landscape of Prehistoric Orkney. In Persson, P., Reide, F., Skar, B., Breivik, H. M. and Jonsson, L. (eds.) The Ecology of Early Settlement in Northern Europe. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing, 393 – 414.

Wherever I turn just now I seem to be collecting examples of the way in which stories, once considered mere fairy tales and myths, may contain an element of description of the past. In some ways, it seems obvious. We use narrative to explain the world around us – today we have several names for these narratives: ‘text books’; ‘academic papers’; ‘theses’, among others. For a long time, we have accepted that there is a second form of narrative, today we call it ‘fiction’, and we regard it very differently; more specifically we assign some of it to a category that encompasses nothing more than imaginative leisure. Fairy tales; mythology; legend: call it what you will, this type of story needs no rooting in reality. In this way, we consider it different to the world of novelistic fiction that we all read for relaxation. Novels are, usually, bounded by the rules of the world; when they are not we assign them special status: science fiction, magic realism and so on. Even these names, however, hint at the way in which it is hard for the writers to move beyond the world they know and love.

Fairy tales are often different. Strange things happen and it can be hard to identify with the settings, actions, and motives of the protagonists. It is sometimes difficult to imagine the minds that conjured up such outlandish ideas. One thing we are usually agreed upon is that these stories are old. They have been around, apparently, since the mists of time and, no doubt, their weirdness is due in part to the way they have been embellished with telling. How many parents have hushed their children with a bedtime fable, or admonished them with an awful story?

And yet, perhaps we should not be surprised that research around the world is identifying increasing examples where the apparently bizarre domain of an ancient story conceals an element of description that seems to be rooted in reality. These stories often relate to a time when the world was a little different, they often tell us about changes that took place in the landscape. They are being collected from Australia to the Americas and locations in between. In Africa and India there are accounts of the submergence beneath the waves of ancient temples and cities. In Atlantic Canada the Mi’kmaq tell of the tensions between Glooscap (a local hero), Beaver, and Whale which led to the breaching of the inner bay of the Minas Basin and infiltration of the tides from the Bay of Fundy. There are many stories from the coastal peoples of Australia, some surprisingly similar: the Aboriginal inhabitants of the Wellesley Islands recount that you could walk out to their island home before the inundation of the sea which was due to the actions of Garnguur, ‘the seagull woman’.

Nearer to home, the land of Cantre’r Gwaelod is said to have extended westwards from the present coastlands of Wales, in the area of Cardigan Bay, and many stories and poems tell of its loss. In my home archipelago of Orkney, the Bay of Otterswick in the island of Sanday was reputedly once home to a great forest, a fact recently confirmed by fieldwork which uncovered the remains of trees subsequently dated to c. 6,500 years ago.

These stories fascinate me because they were originally recounted by people for whom the configuration of the world was truly different. In many cases, it seems they saw strange and scary events and needed to explain them. The tales give voice to the people of the past in a way that archaeology is only just beginning to understand. Of course they have changed in the telling: often exaggerated, bent, augmented and tweaked, we can’t use them as a direct retelling of the past. But, the ultimate irony of archaeology is that, while we seek to learn about people, we have to achieve it through the study of inanimate objects. People, the essence of humanity, lie a long way from the sherds of pottery, stone flakes and soil discolorations that we enthuse over. And yet, strangely, in the current application of geoscience research to the investigation of oral histories, a small sense of the colour and depth of life in the past is beginning to break through.

New Paper out on the development of the landscape around Ness of Brodgar.

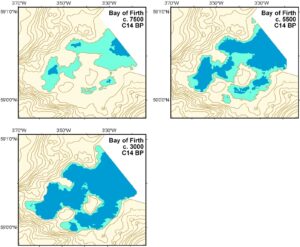

Wickham-Jones, C.R., Bates, M., Bates, R., Dawson, S. and Kavanagh, E. 2016 People and Landscape at the Heart of Neolithic Orkney. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 31 (2), 26-47.

Together with my colleagues, I’ve been working on a paper to discuss the results of our work on landscape change around the Ness of Brodgar, particularly relating to the Loch of Stenness. We published the tekky detail this time last year, and we were keen to explore what it might mean with relation to the Neolithic communities of the area and the siting of the monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney. You really have to read the paper to get the full detail, but in essence our landscape reconstructions document the penetration of marine conditions into the dry land world of the Neolithic farmers at the heart of the islands. Given the emerging evidence for the ‘slighting of the sea’ in the Early Neolithic, it is fascinating that this fragile spot became so important to the island community.

It is possible to order a copy of the Landscape issue of Archaeological Review from Cambridge here. But I can let people have a pdf of our paper for individual research interests – just email me (my email address is on the home page).

You must be logged in to post a comment.