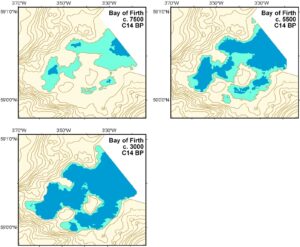

The submerged landscape touches us all, wherever we work. We need to bring a basic understanding of the original lie of the land to our site analyses. However, therein lies a problem. In many places, current understanding of the past position of the coast relies on the application of broadscale models drawn up for general areas such as the North Sea basin. These models are useful, but they are low resolution and cannot provide the level of detail necessary to examine the locale or behaviour of a specific human community. Yet despite the relative simplicity of obtaining the data necessary to build at least a basic idea of the change at any particular location many reports publish speculative maps that lack information.

While the recognition of past landscape change that these entail is clearly ‘a good thing’, the actual value of such reports is limited. They can give us an idea of ‘what might have happened’, but they cannot tell us much about ‘what is likely to have happened’. Without data it is impossible to outline the likely position of the coast at any one time, the processes and rates of landscape change that impacted on a community, or the precise relationships between people and their environment.

The nature of archaeology has changed to embrace such a wide range of specializations. Once upon a time it was not uncommon to undertake an excavation with little palaeoenvironmental analysis. Now, most excavation reports have sections to cover palynology and a whole series of geoscience techniques that help us to understand the formation of the site and its position in the surrounding landscape. Where this landscape extends to the underwater world the techniques are, perhaps, even more specialized, but no less essential. These, hopefully, will be the next elements to be added to the box of tricks that we all like to draw upon.

We have absorbed so much into our profession. We analyze skeletal material for isotope evidence that can help to elucidate diet and origin, we take readings of hearth material for dating purposes, we scan soil samples for elements that help to indicate periods of wet or dry climate. It is fascinating to watch a technique move from ‘amazing’ potential, to essential undertaking. Hopefully, over the coming years we will begin to understand the limitations of modelling and make sure that we always make use of geoscience data collected at an appropriate scale for our research questions. When we are dealing with an individual site or community we need to think about the relevant landscape. This can add to the expense, yes, but surely we all have a duty to do our best by the sites that we are, after all, destroying, in our quest for information.

You must be logged in to post a comment.