Intrigued by the emerging evidence for Late Upper Palaeolithic activity in Scotland, Torben Bjarke Ballin and I have put together a short paper which was published earlier this week in the Journal of Lithic Studies. We are particularly Continue reading Searching for the Scottish Late Upper Palaeolithic

Category: Palaeolithic

Palaeolithic explorers in Orkney

I put together a wee lecture for Radio Orkney last night on the findings of Late Upper Palaeolithic tanged points in Orkney and how they push our understanding of the earliest human exploration of Orkney back to some 13,000 years ago. It lasts for about half an hour. You can listen to it here. Please note that the image Radio Orkney has used to illustrate it is of a handaxe that was found on the beach some years ago and is not actually appropriate to the lecture (it is not likely to be an in situ find, and would be many millennia earlier if it was). I did put together a few images to go with the lecture, they have not been posted with the lecture, but if you would like to get them then just email me and I will let you have a copy – they might relieve the tedium of listening to me droning on for half an hour!

The Power of One

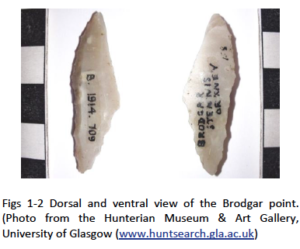

Publication of the tanged point from Brodgar, Orkney, by Torben Bjarke Ballin and Hein Bjartmann Bjerck in the Journal of Lithic Studies has made me ponder on our attitude to isolated finds. The authors suggest that this flint arrowhead adds weight to the body of evidence for Palaeolithic activity in Scotland. To understand the significance of this you have to realise that tanged points occupy a semi mythological status in Scotland, adding apparent weight to elusive evidence for the earliest human activity in the country.

This particular piece was originally published (with two others from separate sites) as Palaeolithic by Livens in 1956, but as it was subsequently lost it has been impossible to investigate his claims. Recently, however, it has been rediscovered, mis-catalogued, in the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow (have a look at it here).

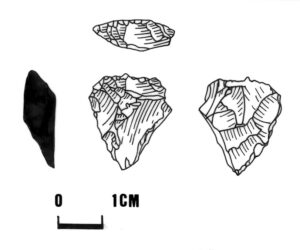

When I studied archaeology, the idea that Scotland had an antiquity that stretched back to the Mesolithic was considered doubtful for the north – to suggest even older occupation during the Palaeolithic was truly daring. I’m happy to say that we now have a respectable number of tanged points from various sites across Scotland, and, though none comes with an associated in-situ assemblage, there is increasing evidence for activity during the Palaeolithic, including the on-going excavation by Steven Mithen and Karen Wicks of an Ahrensburgian type assemblage at Rubha Port an t-Seilich on the west-coast island of Islay.

But, how much evidence is evidence? Single finds, from any other period (and perhaps in any other place) would rarely be considered compelling. Don’t get me wrong. I’m a great fan of the single find – a good part of my archaeological reputation has been built on a single find; one that sits in stately isolation in an even greater landscape than the Brodgar point. In 1986 I co-authored publication of a small and insignificant scraper that has since become known as ‘the North Sea Flint’. It was found below some 134m of sea water in the upper sediments of a core recovered during oil prospection roughly half way between Shetland and Norway. At first we toyed with the idea that this represented some prehistoric tragedy as a lone fisherman was swept out to sea and drowned. Or perhaps it had been lost from the hand of a Victorian collector, proudly displaying it to friends on board a North Sea steamer. Soon we realized that the location from which it had been retrieved would have been dry land and available for settlement towards the end of the last great Ice Age. So, we postulated the early population of a whole land mass (later to be named Doggerland by Bryony Coles) on the basis of a single flint. There were, at the time, no other finds from the northern part of Doggerland and though in recent years there is increasing evidence from the southern North Sea, the northern section is still, largely, unexplored.

There are many reasons why archaeological evidence might be thin on the ground for the Upper Palaeolithic in Scotland. Population density was small and communities were highly mobile. Some sites may have been short lived; some may not have resulted in the deposition of artefactual material. Much of what we know about the communities elsewhere in north west Europe suggests that people were at home on the plains, following and hunting herds such as reindeer. Scotland, with its mountainous terrain was right at the edge of the territory in which they were most comfortable. And, of course, it was a long, long time ago: sites have been affected by a multitude of geomorphological and taphonomic processes since then which will have worked to dismantle the evidence.

So, perhaps we should congratulate ourselves on the way in which our archaeological skills have been honed to the extent that we can recognise and recover any evidence at all, patchy though it is. But I’m not sure about this. There is a good Palaeolithic record from England and Wales and I don’t think archaeologists there make excuses for a paucity of sites. No one nowadays doubts that groups of Upper Palaeolithic hunters did roam across Scotland (or I don’t think they do). So, what is going on? Perhaps we should start by looking at the way in which we undertake our Palaeolithic investigation. Or rather, perhaps we should consider the way in which we don’t do it. ScARF highlighted the problems with finding and managing sites that comprise mainly stone tools and they were focussing on the Mesolithic. I don’t think we have come to terms at all with the possibility that there might actually be a Palaeolithic record here.

Until we do we shall continue to idolize the power of one, by creating a Palaeolithic that is truly ‘join-the-dots’ archaeology as we try to (re)create whole landscape(s), with chronological and geographical depth, out of isolated finds and occasional serendipitous scatters of broken and abandoned flints.

Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Scotland in a nutshell

I’ve been asked to provide a five-minute summary of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Scotland. It is an interesting exercise, but it is difficult. I’ve not done it entirely to my satisfaction, but here is the ten-minute version!

The period between 14,000 and 6000 years ago was a time of considerable environmental transformation. Change was very much the norm for those who lived in Scotland at the end of the Palaeolithic and into the Mesolithic.

Perhaps the main transformation was the ending of the last great Ice Age and in some ways all things lead from this so we need to understand it. Another, relevant to the mobile hunter-gatherers of northwest Europe, was the generally rising sea-levels that led to the loss of Doggerland. But to highlight these masks a dynamic world that encompassed a wide range of change, all of which was relevant to the communities seeking to survive in Scotland – we can’t separate people from their environment. When considering human activity at any time we have to be fully aware of the world in which people lived and of the long-term and short-term challenges they faced. Among the relevant challenges for this period are the climatic deterioration known as the 8.2 ka cold event, which had widespread impact including a drop in temperature, increased windiness, and decreasing rainfall, though it was short and sharp – lasting for around two hundred years.

It is also important to remember that broadscale accounts mask specific events such as bad winters, droughts, winds and storm surges, and we do need to hold these in mind because it is precisely these events that impact upon the lives of individual communities. The single event that has received perhaps the most attention in recent years is the tsunami associated with the Storegga Slide. Dated with increasing precision to around 6150 BC it would have had devastating impact. Tsunami deposits have been found at heights over 20m in Shetland and it is likely that there was a knock on effect everywhere, compounded by the fact that it was unpredictable and occurred during the height of the 8.2 ka cold event.

Moving to the people: the inhabitation of Scotland during the Late Glacial has been a matter of some debate characterised by increasing evidence from finds of stone tools, of periodic human activity prior to the Younger Dryas (the re-establishment of glacial conditions between roughly 10,500 BC – 9700 BC), and culminating in the on-going excavation by Steven Mithen and Karen Wicks of an Ahrensburgian type assemblage (about 12,000 years old) from Rubha Port an t-Seilich on the west-coast island of Islay. The precise arrival of Mesolithic communities in Scotland is equally shrouded in uncertainty. We follow the stone tools because they have survived but do we always understand them? Broad blade microlith technologies of a type used to identify the earliest Mesolithic communities in England do occur in Scotland but they are rare and, as yet, not securely dated so that interpretation of the activity that led to them is weak. Narrow blade microlith technologies are more common and, in general, may be dated from the mid ninth millennium BC onward. Setting aside the theoretical weaknesses of equating tool technology with cultural community, the overall picture is one of increasing evidence for hunter-gatherer groups, and probable diversity between communities, from this period onwards.

A challenging aspect of the evidence for Mesolithic Scotland is the way in which the majority of sites are coastal, and we have to ask ourselves whether this reflects archaeological reality? The existing evidence suggests the presence of highly specialised communities well able to exploit the marine and littoral resources, and for whom water-born transport may have facilitated coastal mobility, but how much did they penetrate the uplands? We assume they did: emerging data illustrates the use of the montane interior even during times of climatic stress such as the 8.2 ka event. Are these the same groups? In some places it may well be that a single group made use of a particular river system, but in other areas research suggests that separate coastal and inland groups existed.

One aspect is notable: the growing evidence for structural remains excavated over the last 30 years. Much has been made of the traces of post-built circular structures that are interpreted as semi-permanent. In Scotland these occur within the ninth millennium BC, though that at Mount Sandel in the north of Ireland has recently been re-dated to the early eighth millennium BC. They seem to have been in use during a time of stable climatic conditions, yet at a time when relative sea-level change (and concomitant land loss) was likely to have been most rapid. Their occupation occurs prior to the 8.2 ka cold event and to the Storegga tsunami. Many, but not all, occur in close proximity to the present coast.

These structures are not the only evidence we have for Mesolithic habitation however, other remains include light shelters and foundation slots. They occur across Scotland from Orkney to the Solway Firth. Most are found near to the coast (perhaps reflecting the evidence in general), but inland sites are being discovered (most recently at high altitude in the Cairngorms). With the exception of the site at Morton (where the interpretation is difficult), all yielded narrow blade microliths. Many sites have early dates, back to some of the earliest evidence for the Mesolithic in Scotland, but there are sites with later dates such as Cnoc Coig, though in general the later Mesolithic archaeology is less well represented and less well understood. On some sites a combination of different structural remains has been recovered.

Interpretation of the more robust structures has proved challenging to Mesolithic archaeologists seeking to validate paradigms of a mobile society. One solution has been to tie them to evidence of environmental instability; are they associated with increased competition for resources as the Doggerland landmass diminished? Actually I think it is more likely that they are a result of stability. Be that as it may, if we wish to create a more complete understanding of this period then it is necessary to consider all the evidence and not select specific ‘interesting’ elements.

Physical evidence apart – what about the people? There is very, very little skeletal evidence for Mesolithic Scotland. So, how many people were there? Estimation of population size where the archaeological record is demonstrably patchy is fraught with difficulty. In 1962 Atkinson suggested a total population for Scotland of about 70, but this has long been considered an underestimate. Tolan-Smith suggested that by the end of the seventh millennium BC population had reached maximum carrying capacity, but he does not actually say how he calculated this, nor give any numbers. More recently Wicks and Mithen have tackled the problem in a different way, using radiocarbon dates as a proxy; they don’t provide absolute numbers either, but their work is interesting because by postulating the possible reduction of population in western Scotland during, and after, the 8.2 ka cold event they are suggesting that population density was large enough to be challenged by the deterioration in environmental conditions.

To close, it is very easy to present the Mesolithic as some sort of utopia. But we have to be wary of this. We are dealing with a long period, a long time ago. Ethnographic work on hunter-gatherers should remind us that there is no average community, no average territory and no average life-style. Nevertheless, what we do see is that life as a hunter-gatherer is finely balanced. Sophisticated knowledge of the environment is weighed against all sorts of issues such as population density, environmental stability, and mobility in order to build a viable long-term lifestyle. This can be knocked out of kilter. Change, in any one part of the system, invariably affects all other aspects. It is an exciting aspect of modern archaeological studies that rather than simply gathering data we can now start to play around and look at elements such as this. We assume that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were consummate survivors (how else would we be here), life was undoubtedly difficult, but we have started to see examples of adaption and that is very gratifying.

Ancient Scotland: pushing back the boundaries

Archaeology has changed so much since I studied at Edinburgh. That is a good thing – at least our work is leading to new finds and new thoughts.

Earlier this month Steven Mithen and Karen Wicks from the University of Reading released a press statement about their excavations at Rubha Port an t-Seilich on the island of Islay where finds of a particular style of stone tools point to human activity in the west of Scotland towards the end of the Late Glacial Period about 12,000 years ago. Technically, we call this period the Ahrensburgian, though of course we have no idea how the people would have styled themselves.

We do have other hints that people were in Scotland at the time, but, so far there is really very little evidence from this period. Luckily, people have always been slaves to fashion and archaeologists can make use of this; characteristic stone tools from this period do turn up, but they tend to be found as isolated finds, perhaps from hunting accidents. Rubha Port an t-Seilich provides the first opportunity to excavate a site in detail, so it is a significant find.

Conditions in northwest Europe at the time were chilly, with ice caps not far away. The landscape in this part of Scotland is likely to have comprised tundra grassland with cold winters but milder summers. Sites elsewhere show that the reindeer hunters of earlier periods had diversified to exploit the coast, and this perhaps explains the arrival of a group in Islay. Research indicates that the coasts of Scotland were free of extensive sea ice cover at this time. The evidence suggests that individual communities might travel long distances in order to exploit the resources around their territory. These people were sophisticated hunters, well equipped to be able to survive in an environment that we would find harsh. Nevertheless, the exploration of new lands was no mean feat.

When I studied archaeology in the 70s there was no evidence at all that Scotland had been inhabited this early. Indeed, there was little evidence from the subsequent Mesolithic period, and general wisdom suggested that the north and west of Scotland would have been uninhabited before the arrival of the first farmers some 6000 years ago. One reason for the lack of Mesolithic material was the lack of archaeologists working on it. Quite apart from the fact that it was the period that interested me most, I have always thought that I made a canny move setting out to study the period that most people found boring. It meant that whatever I did was likely to make an impact. It is not quite so easy for those embarking on an archaeological career today. I’m happy to report that there is now a strong and numerous band of happy Mesolithic archaeologists and that the results of their work across Scotland (even in the north and the west) mean that Mesolithic archaeology is full of interesting discussion and theory!

Hopefully the recent discoveries in Islay mean that we are about to witness the pushing back of the boundaries of ancient Scotland even further.

You can read more about Steve and Karen’s work in their recent paper here.

The anatomy of hunting

I’m reading Richard Nelson’s little book of stories about hunting in the north, Shadow of the Hunter. It makes fascinating reading; the stories are gentle, nothing too gripping, but it evokes a powerful sense of landscape, of different types of snow and ice, and of the decisions made by those who rely on their own senses to make a living there.

It brings home the way in which a successful hunter has to ‘become’ the prey, relying on empathy with the targeted animal in order to anticipate its movements and make a kill. Indeed he discusses this aspect as part of the everyday round.

I’m also struck by the way in which those who hunt and butcher in order to bring meat and other materials home must have a detailed knowledge of the anatomy and workings of the animals they seek. I know this is blindingly obvious, but it has never sunk in before. It got me thinking about the detail we see on Palaeolithic Cave art and other representations like some of the Pictish designs. Rather than being surprised at the apparent anatomical knowledge displayed by the artists it seems to me that the surprise is when they don’t depict it. The motivation behind more stylized illustration must have been interesting.

Another element of the book is the way in which the stories are played out by men. Women have little role in most of the chapters. This is largely due to the author’s own aims: he set out to record specifically hunting techniques. I know there are other books that record the role of women, like Daughters of Copper Woman and now I must go and revisit them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.