I’ve been asked to provide a five-minute summary of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Scotland. It is an interesting exercise, but it is difficult. I’ve not done it entirely to my satisfaction, but here is the ten-minute version!

The period between 14,000 and 6000 years ago was a time of considerable environmental transformation. Change was very much the norm for those who lived in Scotland at the end of the Palaeolithic and into the Mesolithic.

Perhaps the main transformation was the ending of the last great Ice Age and in some ways all things lead from this so we need to understand it. Another, relevant to the mobile hunter-gatherers of northwest Europe, was the generally rising sea-levels that led to the loss of Doggerland. But to highlight these masks a dynamic world that encompassed a wide range of change, all of which was relevant to the communities seeking to survive in Scotland – we can’t separate people from their environment. When considering human activity at any time we have to be fully aware of the world in which people lived and of the long-term and short-term challenges they faced. Among the relevant challenges for this period are the climatic deterioration known as the 8.2 ka cold event, which had widespread impact including a drop in temperature, increased windiness, and decreasing rainfall, though it was short and sharp – lasting for around two hundred years.

It is also important to remember that broadscale accounts mask specific events such as bad winters, droughts, winds and storm surges, and we do need to hold these in mind because it is precisely these events that impact upon the lives of individual communities. The single event that has received perhaps the most attention in recent years is the tsunami associated with the Storegga Slide. Dated with increasing precision to around 6150 BC it would have had devastating impact. Tsunami deposits have been found at heights over 20m in Shetland and it is likely that there was a knock on effect everywhere, compounded by the fact that it was unpredictable and occurred during the height of the 8.2 ka cold event.

Moving to the people: the inhabitation of Scotland during the Late Glacial has been a matter of some debate characterised by increasing evidence from finds of stone tools, of periodic human activity prior to the Younger Dryas (the re-establishment of glacial conditions between roughly 10,500 BC – 9700 BC), and culminating in the on-going excavation by Steven Mithen and Karen Wicks of an Ahrensburgian type assemblage (about 12,000 years old) from Rubha Port an t-Seilich on the west-coast island of Islay. The precise arrival of Mesolithic communities in Scotland is equally shrouded in uncertainty. We follow the stone tools because they have survived but do we always understand them? Broad blade microlith technologies of a type used to identify the earliest Mesolithic communities in England do occur in Scotland but they are rare and, as yet, not securely dated so that interpretation of the activity that led to them is weak. Narrow blade microlith technologies are more common and, in general, may be dated from the mid ninth millennium BC onward. Setting aside the theoretical weaknesses of equating tool technology with cultural community, the overall picture is one of increasing evidence for hunter-gatherer groups, and probable diversity between communities, from this period onwards.

A challenging aspect of the evidence for Mesolithic Scotland is the way in which the majority of sites are coastal, and we have to ask ourselves whether this reflects archaeological reality? The existing evidence suggests the presence of highly specialised communities well able to exploit the marine and littoral resources, and for whom water-born transport may have facilitated coastal mobility, but how much did they penetrate the uplands? We assume they did: emerging data illustrates the use of the montane interior even during times of climatic stress such as the 8.2 ka event. Are these the same groups? In some places it may well be that a single group made use of a particular river system, but in other areas research suggests that separate coastal and inland groups existed.

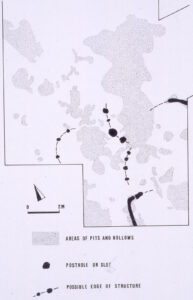

One aspect is notable: the growing evidence for structural remains excavated over the last 30 years. Much has been made of the traces of post-built circular structures that are interpreted as semi-permanent. In Scotland these occur within the ninth millennium BC, though that at Mount Sandel in the north of Ireland has recently been re-dated to the early eighth millennium BC. They seem to have been in use during a time of stable climatic conditions, yet at a time when relative sea-level change (and concomitant land loss) was likely to have been most rapid. Their occupation occurs prior to the 8.2 ka cold event and to the Storegga tsunami. Many, but not all, occur in close proximity to the present coast.

These structures are not the only evidence we have for Mesolithic habitation however, other remains include light shelters and foundation slots. They occur across Scotland from Orkney to the Solway Firth. Most are found near to the coast (perhaps reflecting the evidence in general), but inland sites are being discovered (most recently at high altitude in the Cairngorms). With the exception of the site at Morton (where the interpretation is difficult), all yielded narrow blade microliths. Many sites have early dates, back to some of the earliest evidence for the Mesolithic in Scotland, but there are sites with later dates such as Cnoc Coig, though in general the later Mesolithic archaeology is less well represented and less well understood. On some sites a combination of different structural remains has been recovered.

Interpretation of the more robust structures has proved challenging to Mesolithic archaeologists seeking to validate paradigms of a mobile society. One solution has been to tie them to evidence of environmental instability; are they associated with increased competition for resources as the Doggerland landmass diminished? Actually I think it is more likely that they are a result of stability. Be that as it may, if we wish to create a more complete understanding of this period then it is necessary to consider all the evidence and not select specific ‘interesting’ elements.

Physical evidence apart – what about the people? There is very, very little skeletal evidence for Mesolithic Scotland. So, how many people were there? Estimation of population size where the archaeological record is demonstrably patchy is fraught with difficulty. In 1962 Atkinson suggested a total population for Scotland of about 70, but this has long been considered an underestimate. Tolan-Smith suggested that by the end of the seventh millennium BC population had reached maximum carrying capacity, but he does not actually say how he calculated this, nor give any numbers. More recently Wicks and Mithen have tackled the problem in a different way, using radiocarbon dates as a proxy; they don’t provide absolute numbers either, but their work is interesting because by postulating the possible reduction of population in western Scotland during, and after, the 8.2 ka cold event they are suggesting that population density was large enough to be challenged by the deterioration in environmental conditions.

To close, it is very easy to present the Mesolithic as some sort of utopia. But we have to be wary of this. We are dealing with a long period, a long time ago. Ethnographic work on hunter-gatherers should remind us that there is no average community, no average territory and no average life-style. Nevertheless, what we do see is that life as a hunter-gatherer is finely balanced. Sophisticated knowledge of the environment is weighed against all sorts of issues such as population density, environmental stability, and mobility in order to build a viable long-term lifestyle. This can be knocked out of kilter. Change, in any one part of the system, invariably affects all other aspects. It is an exciting aspect of modern archaeological studies that rather than simply gathering data we can now start to play around and look at elements such as this. We assume that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were consummate survivors (how else would we be here), life was undoubtedly difficult, but we have started to see examples of adaption and that is very gratifying.

You must be logged in to post a comment.