Still ranting!

Bayesian dating is a new, and useful tool in the archaeological box of tricks. And like any new toy – we are keen to make use of it. But, it is a specialised piece of kit and we need to be careful that we know exactly what we are doing. I’m amazed by the number of times people say: ‘but why did you not use Bayesian dating’. In most cases the answer would be that it is not appropriate for poorly contexted samples on a site with shallow stratification. But I’m too polite to say that. Too many archaeologists seem to consider Bayesian dating as a simple means of getting more accurate dates.

Even when undertaking the old-fashioned application of radiocarbon assay it was necessary to remember to constrain our data carefully so that we understood the context of the sample we were dating and therefore exactly what the date might relate to. Is the pit-fill contemporary with the digging of the pit? Is the deposit on a house-floor related to the use of the house, or is it some sort of dumping after the house had gone out of use? Is the wood heartwood from an aged tree? Has the wood (or bone for that matter) been curated over a period of years? So many things to take into account.

However we use radiocarbon assay, and whatever method we use, we should never use it unquestioningly.

I know I come over as obsessed with all of this. But I learnt of the dangers of type-fossils and pre-conceived ideas early on in my career as an archaeologist.

When I studied archaeology we were taught that there was no Mesolithic occupation to speak of in highland Scotland. Not long after graduating I had the opportunity to excavate a nice lithic scatter on the island of Rum. The site was defined by the occurrence of a barbed and tanged arrowhead among the lithics, so we drew up a research design to excavate a site that was, clearly (according to the type fossil), Bronze Age. As we sieved our test pits and sorted the residue a lot of flaked stone occurred. It included a lot of small pieces with tiny retouch – microliths. But I knew they should not be there because microliths were Mesolithic and did not occur in the Bronze Age. And I had learnt at university not to expect Mesolithic occupation that far north. Even when I filled in the radiocarbon forms to send our precious carbon samples off for assay I noted that the predicted date range lay within Bronze Age parameters. I remember that well.

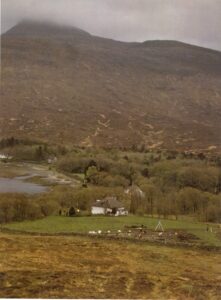

Imagine my surprise therefore when the dates came back: a nice little sequence around 8500 years ago. This was long before the Bronze Age. Indeed, it sat within the Mesolithic but was early even for Mesolithic Scotland and unknown that far north. I can remember thinking that if I didn’t know there was no Mesolithic in the area I’d think the site was Mesolithic. Of course, the penny eventually dropped, we continued to excavate a fabulous Mesolithic site (you can read the report for free here), and many other people have since examined other Mesolithic sites around there and even to the north.

But I had another surprise. I thought that my archaeological colleagues would be interested (even pleased) in my findings and so I phoned and wrote to people to tell them about the site and the dates. Curiously, people were divided: some wrote back with hearty congratulations; others were more cautious, telling me that I must have contaminated the samples, that it was just not possible for Mesolithic hunters to have penetrated that for north by that date, and so on. It was, I discovered, hard for some people to give up their fixed ideas of the order of things.

Change is always difficult, but I think we need to be cautious of thinking that we have worked out everything there is to know about the past. We need to be open to new interpretations and ready to rewrite our narratives. We need to remember that it is rarely the type fossils that are wrong, but rather our understanding.

So, the moral of my story is – to keep an open mind. To be open to the unexpected. And to be careful not to set the past into stone. The frameworks that we build to understand the people of the past need constant tweaking. That is what keeps us on our toes. That is what keeps it interesting.

And this is my last post on dating for a while – I promise!

You must be logged in to post a comment.